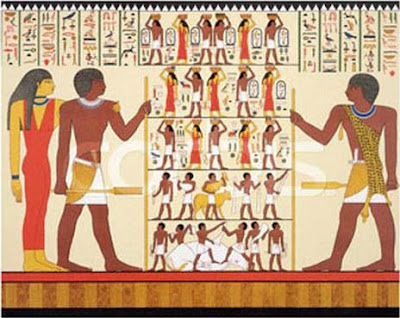

| The art of drawing and relief inscription flourished in ancient Egypt, as evidenced on the walls of temples and tombs. The artist dealt with the wall as a painting surface and tried to utilize all available spaces. This was not the work of a single artist, since the ancient Egyptian painting work was generally done in three stages. Various categories of artists participated, each with his own area of expertise. In the first stage, the basic primary lines that shape the features of the figure were drawn. In the second phase, coloring was done, starting with the wider areas and progressing to the details of the painting. Then the final phase was drawing fine lines and showing details. We can generally say that there were no distinctions between drawing, painting, and inscription. Even if we can differentiate inscriptions into two types, namely carving and engraving, either one of these two methods had to be preceded by drawing to make the original design of the figure and determine its basic lines. The coloring method used colored pastes to fill in the spaces in the drawing. The Egyptian artist often used color-fixing materials to prolong the life of colors. Because art was related to religious architecture, the artist took interest in portraying gods, glorifying them through presenting various types of offerings and recording prayers and recitations. At the same time, he portrayed different aspects of daily life that the deceased person may enjoy in his tomb and carry with him to the hereafter. Such scenes were not specific events or special moments of significance to the deceased, but were general scenes representing activities such as agriculture, hunting, herding, playing, or quarreling. In portraying people, the artist adopted the law of ratios, which remained in use until the Twenty-sixth Dynasty. The artist divided the surface into equal squares on which he drew the general lines of the human body. According to certain ratios between the body parts, he filled in the squares until his work was completed. It was found that portraying the profile view was an ideal way to present all parts of the body. However, profiling was not a fixed rule. The need to show all details often necessitated the portrayal of the front view. In some cases, the artist combined both methods, for example, by drawing the head in profile, the shoulders in front view, and the lower part in a side view. In the Greco-Roman era, the link between these arts and religion continued. One of the most important features of Hellenistic art was the inscription of religious and mythical subjects on coffins. In addition, portrayal of human faces, similar to current portrait art, was one of the most significant additions in common use in that era. Also in use were the masks of mummies and colored funeral masks, which are portraits of the deceased person. These were placed directly on the face of the deceased, representing the actual features of that person, so that the spirit could identify the body. In many cases, coffins were made in the form of the deceased person. In the third century AD, an icon representing the person was hung in his house until his death, when it was then fixed to his coffin. Such icons disappeared after the fourth century AD, but appeared again in the sixth century. The beginning of Coptic portrait art can be traced back to the second century AD, starting in the tombs of early Christians. At first, the portrayed subjects were not directly related to the new religion, but Bible stories and symbolic themes gradually appeared until Jesus Christ and the Virgin Mary were clearly and directly portrayed. Portraits can be divided into three types, according to the method adopted. The tempera method, which was utilized since the Pharaonic era, used sticky materials such as glue or egg white to provide colors with thickness. The encaustic method is a Greek method introduced to Egypt in the Greco-Roman era and it spread to Greek cities such as Alexandria, Faiyum, and Shaikh Ebada. It was based on mixing colors with wax and in some cases, a small amount of oil was added, which gave the drawing a glossy appearance to look like oil paintings. This method remained in use until the eleventh century. The third method is the fresco, utilizing water colors. It is a simple method based on mixing colors directly with water without any other medium. The colors are applied to the wall before it dries, so that both would dry together. This method appeared in the Christian era, although it did not last for long. Oil painting as we know today, which is a cheaper and easier method, did not appear until the Byzantine era. |

Egyptian relics - The Curse of the Pharaohs

- the secret of mummification - Magic at the Pharaohs - Luxor - Sphinx -

Pyramids - The Temple of Karnak - The Temple of Abu Simbel - Temple of

Ramses II - Akhenaten - Tuthmosis III - Tutankhamun - Pharaoh -

Nefertiti - Cleopatra - Nefertari - Hatshepsut -

|

No comments:

Post a Comment