History of Egyptology in the Valley

The Classical Greek writers Strabo and Diodorus Siculus were able to report that the total number of Theban royal tombs was 47, of which at the time only 17 were believed to be undestroyed. Pausanias and others wrote of the pipe-like corridors of the Valley, tombs into which travelers could descend and admire the wall decorations.

Some of these travelers left their names and other marks. The earliest datable graffito in the Valley was found in the tomb of Ramesses VII, and can be dated to 278 BCE, and the latest, left by a governor of Upper Egypt was dated to 537 ACE. The French scholar Jules Baillet counted over 2000 Greek and Latin graffiti left over the Classical centuries, along with a lesser number in Phoenician, Cypriot, Lycian, Coptic, and other languages. Almost half of these were found in the tomb of Ramesses VI, who was considered to be the fabled Memnon himself.

After the Arabs came into Egypt in 641 ACE, interest in the Valley waned considerably. It was not until the end of the 16th century that once again travelers began once again to take notice. Although the location of Thebes was clearly marked on a map of 1595, in 1668 a Father Charles Francois visited "the place of the mummies" and apparently did not realize its significance. It was left to another Frenchman, Father Claude Sicard, head of the Jesuit Mission in Cairo, traveling in Egypt between 1714 and 1726, who visited in the Valley in 1708 and located 10 open tombs including that of Ramesses IV. He wrote of the extensive wall paintings and their colors.

Father Claude Sicard

Sicard’s notes for the most part were unfortunately lost, and thus the first significant published account of the Valley was left to an Englishman named Richard Pococke in 1743. He apparently noted signs of about 18 tombs, though believing that only nine of these could be entered. In 1768 a Scotsman named James Bruce visited Luxor and explored the Valley. He visited the tombs of Ramesses IV and of Ramesses III, henceforth known as "Bruce’s Tomb." The principal feature of the latter tomb, for Bruce, were the fresco scenes of three harps

William George Brown visited the Valley in 1792, and he left his name in the tomb of Ramesses III. He also recounted one of the few extant accounts of contemporary Arab interest and excavation at the site. Browne wrote that the site had been explored "in the last 30 years" by a certain son of a Sheikh Hamam, but it is unknown whether or not this person was successful. Browne also described several tombs to which he had access, three of which did not seem to tally with descriptions given by Richard Pococke.

After Napoleon’s Expedition in 1798, two Frenchmen named Prosper Jollois and Edouard de Villiers du Terrage recorded the position of 16 tombs. For the first time the existence of a western branch of the valley was recorded, including the tomb of Amenhotep III. Jollois and de Villiers were to publish their works in the 19 volume Description de l’Egypte

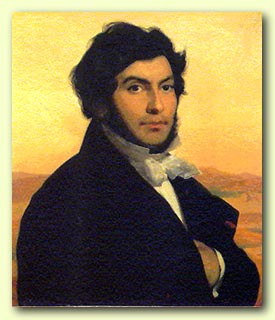

Jean Francois Champollion

One of the great names of early Egyptology has to be that of Champollion, for his work in translating the ancient hieroglyphic symbols on the Rosetta Stone and thus opening the door to a greater understanding of the lives of these people. But though this work and his beautiful drawings published in his Monuments de l’Egypte et de la Nubie left a brilliant legacy for scholars who followed him, he also left a legacy of shoddy and misguided destruction. Champollion and his companion Rossellini removed two scenes from the tomb of Seti I, which they brought to the Louvre and to a museum in Florence.

Giovanni Belzoni, called the Patagonian Samson, was the first modern-era European to visit the Valley of the Kings. He was sponsored by the Englishman Henry Salt, Consul-General in Egypt in 1816. Among other treasures, Belzoni removed from Egypt the sarcophagus of Ramesses III from "Bruce’s Tomb," and it now lies in the Louvre and the Fitzwilliam Museums. To give him some credit, Belzoni also not only confirmed the presence of the 47 tombs known to Classical writers, but added a further 8 tombs to that list, including those of King Ay, Prince Mentuherkhepshef, and Ramesses I. Belzoni’s most well-known find in the Valley was the tomb of Seti I, the finest so far found

Giovanni Belzoni

James Burton was a contemporary of Wilkinson in Thebes. He began a clearance of the tomb listed as KV20, which he had to abandon due to "bad air" and only later would be proven by Howard Carter to be the tomb of Thutmose I and Hatshepsut. Burton also began a superficial examination of the tomb later called KV5. This tomb would wait until the 20th century to prove itself as the largest tomb to-date, most probably cut to serve the family of Ramesses II. At least 50 of his children have been found so far to have been buried therein. Burton published no records of his work, though some 63 volumes of his notes and drawings were given to the British Museum upon his death in 1862.

Karl Richard Lepsius followed both examples, that of scholarly recording and that of removing artifacts from their original place of rest. In 1844, Lepsius led a Prussian-backed expedition to Egypt. After years of exploring, mapping, and drawing pyramids, tombs, and monuments, including the Valley of the King tombs, Lepsius returned and produced the twelve-volume work Denkmaler aus Agypten und Athiopien. But he also sent out of Egypt 15,000 pieces, and at one time, overthrowing a decorated column in Seti’s tomb merely in order to remove a portion of it, leaving the rest in wreckage on the floor.

After Belzoni’s escapades, scholars began to emphasize recording and studying what had been found in the Valley, rather than simply searching for more tombs. John Gardner Wilkinson, born in Chelsea, England in 1797 excavated in the Valley in 1824 and in 1827-28.at his own expense. Except for the West Valley, which he numbered separately, Wilkinson physically assigned a number to each tomb entrance, still visible today. Tombs KV1-21 are marked on the map of the main valley in his Topographical Survey of Thebes of 1830.recorded in 1827 that 21 tombs were open to view, listing them in chronological order. He copied scenes and inscriptions and then published the first accurate account of the tombs, titled Topography of Thebes, in 1830.

In the latter half of the 19th century, this plundering would come to a close. Auguste Mariette laid the foundations of a national Egyptian museum and for a governmental antiquities service. It was Mariette who discovered the Serapeum, the burial place at Memphis of the sacred Apis bulls, and the intact burial of Queen Ahhotep, mother of Ahmose, the founder of the New Kingdom. But Mariette’s greatest contribution to Egyptology was the formation of the Antiquities Service. As Director-General, he was responsible for awarding concessions to all excavators, monitoring all digs, and policing the export of antiquities.

When the first cache of royal mummies was discovered in 1881 at Hatshepsut’s temple of Deir el Bahri, world attention was once and for all focused on the quiet valley, and the first of many new excavations began in the area. Victor Loret arrived in Luxor in 1898. Loret had been appointed as the Director-General of the Antiquities Service, established by Mariette in 1856. Only five days after he began to dig below the cliffs under the Qurn, or "Horn" mountain, his team discovered the tomb of Thutmose III. He added 16 tombs to the map of the principal Valley. He also discovered the second cache of royal mummies within the tomb of Amenhotep II.

But Loret was not well-liked, and upon his resignation Maspero was reinstated. In 1899, Maspero appointed Howard Carter to be Antiquities Inspector for Upper Egypt. His responsibilities were to maintain all the sites of Upper Egypt and to grant concessions for others to dig, rather than having the authority to dig on his own. One of Carter’s claims to fame in this job was that he installed the first electric lighting, handrails, staircases and running boards in the royal tombs.

Financing these improvements required the backing of investors, and one such was the American Theodore Davis. Under his patronage, Carter discovered the royal tomb of Thutmose IV, including a wonderful royal chariot, and the tomb of Hatshepsut herself, containing her sarcophagus and that of her father Thutmose I.

Howard Carter

When Davis persuaded Maspero in 1903 that he could no longer work with Carter, Maspero promoted Carter to Inspector of Saqqara, but Carter resigned six weeks later and never worked for the Antiquities Service again. Maspero replaced him with James Quibell, but he too was eventually replaced, by Arthur Weigall. Weigall was the one who broke through a tomb entrance that Quibell had earlier discovered, to find the rich burial goods and mummies of Yuya, Master of the King’s Horse, and his wife Thuya, the parents of Tiye, wife of Amenhotep III and mother of Amenhotep IV, later to rename himself Akhenaten.

More archaeologists and Egyptologists would follow, and great finds would continue to be made. Many excavators would return to Egypt and add astounding discoveries in the Valley to their earlier finds. Howard Carter was one who kept on working. For all the incredible efforts and discoveries made in the Valley of the Kings, in past decades or within just the past weeks, and all the contributions to the expansion of our knowledge of the funerary practices and literature and of the kingly history of ancient Egypt, all these seem veritably overshadowed by the finds made that relate to just one burial, the tomb and riches of the young King Tutankhamun.

Other Tour Egypt References on the Valley of the Kings

Egyptian relics - The Curse of the Pharaohs

- the secret of mummification - Magic at the Pharaohs - Luxor - Sphinx -

Pyramids - The Temple of Karnak - The Temple of Abu Simbel - Temple of

Ramses II - Akhenaten - Tuthmosis III - Tutankhamun - Pharaoh - Nefertiti - Cleopatra - Nefertari - Hatshepsut -

No comments:

Post a Comment